'Ferdinand de Saussure's Course in General Linguistics is one of the most influential texts of the 20th-century - an astonishing feat for what is, at heart, a series of deeply technical lectures about the structure of human languages. What the Course's vast influence shows, fundamentally, is the power of good interpretative skills.

3 – Value Saussure realized that if linguistics was going to be an actual science, language could not be a mere nomenclature; for otherwise it would be little more than a fashionable version of, constructing lists of the definitions of words. Thus he argued that the sign is ultimately determined by the other signs in the system, which delimit its meaning and possible range of use, rather than its internal sound-pattern and concept. Sheep, for example, has the same meaning as the French word mouton, but not the same value, for mouton can also be used to mean the meal lamb, whereas sheep cannot, because it has been delimited by mutton. Language is therefore a system of interdependent entities.

But not only does it delimit a sign's range of use, for which it is necessary, because an isolated sign could be used for absolutely anything or nothing without first being distinguished from another sign, but it is also what makes meaning possible. The set of synonyms redouter ('to dread'), craindre ('to fear'), and avoir peur ('to be afraid'), for instance, have their particular meaning so long as they exist in contrast to one another. But if two of the terms disappeared, then the remaining sign would take on their roles, become vaguer, less articulate, and lose its 'extra something', its extra meaning, because it would have nothing to distinguish it from.

This is an important fact to realize for two reasons: (A) it allows Saussure to argue that signs cannot exist in isolation, but are dependent on a system from within which they must be deduced in analysis, rather than the system itself being built up from isolated signs; and (B) he could discover grammatical facts through and analyses. Syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations Language works through relations of difference, then, which place signs in opposition to one another. Saussure asserted that there are only two types of relations: syntagmatic and paradigmatic. The latter is associative, and clusters signs together in the mind, producing sets: sat, mat, cat, bat, for example, or thought, think, thinking, thinker. Sets always involve a similarity, but difference is a prerequisite, otherwise none of the items would be distinguishable from one another: this would result in there being a single item, which could not constitute a set on its own. These two forms of relation open linguistics up to, and. Take morphology, for example.

The signs cat and cats are associated in the mind, producing an abstract paradigm of the word forms of cat. Comparing this with other paradigms of word forms, we can note that in the English language the plural often consists of little more than adding an s to the end of the word. Likewise, in syntax, through paradigmatic and syntagmatic analysis, we can discover the grammatical rules for constructing sentences: the meaning of je dois ('I should') and dois je?

) differ completely simply because of word order, allowing us to note that to ask a question in French, you only have to invert the word order. A third valuation of language stems from its social contract, or its accepted use in culture as a tool between two humans. Since syntagmas can belong to speech, the linguist must identify how often they are used before he can be assured that they belong to the language.

Synchronic and diachronic axes To consider a language is to study it 'as a complete system at a given point in time,' a perspective he calls the AB axis. By contrast, a analysis considers the language 'in its historical development' (the CD axis). Saussure argues that we should be concerned not only with the CD axis, which was the focus of attention in his day, but also with the AB axis because, he says, language is 'a system of pure values which are determined by nothing except the momentary arrangements of its terms'.

To illustrate this, Saussure uses a metaphor. We could study the game diachronically (how the rules change through time) or synchronically (the actual rules). Saussure notes that a person joining the audience of a game already in progress requires no more information than the present layout of pieces on the board and who the next player is. There would be no additional benefit in knowing how the pieces had come to be arranged in this way.

Geographic linguistics A portion of Course in General Linguistics comprises Saussure's ideas regarding the geographical branch of linguistics. According to Saussure, the geographic study of languages deals with external, not internal, linguistics. Geographical linguistics, Saussure explains, deals primarily with the study of linguistic diversity across lands, of which there are two kinds: diversity of relationship, which applies to languages assumed to be related; and absolute diversity, in which case there exists no demonstrable relationship between compared languages. Each type of diversity constitutes a unique problem, and each can be approached in a number of ways.

For example, the study of Indo-European languages and Chinese (which are not related) benefits from comparison, of which the aim is to elucidate certain constant factors which underlie the establishment and development of any language. The other kind of variation, diversity of relationship, represents infinite possibilities for comparisons, through which it becomes clear that dialects and languages differ only in gradient terms. Of the two forms of diversity, Saussure considers diversity of relationship to be the more useful with regard to determining the essential cause of geographical diversity. While the ideal form of geographical diversity would, according to Saussure, be the direct correspondence of different languages to different areas, the asserted reality is that secondary factors must be considered in tandem with the geographical separation of different cultures.

Ferdinand De Saussure Linguistic Theory

For Saussure, time is the primary catalyst of linguistic diversity, not distance. To illustrate his argument, Saussure considers a hypothetical population of colonists, who move from one island to another. Initially, there is no difference between the language spoken by the colonists on the new island and their homeland counterparts, in spite of the obvious geographical disconnect. Saussure thereby establishes that the study of geographical diversity is necessarily concentrated upon the effects of time on linguistic development. Taking a monoglot community as his model (that is, a community which speaks only one language), Saussure outlines the manner in which a language might develop and gradually undergo subdivision into distinct dialects. Saussure's model of differentiation has 2 basic principles: (1) that linguistic evolution occurs through successive changes made to specific linguistic elements; and (2) that these changes each belong to a specific area, which they affect either wholly or partially. It then follows from these principles that dialects have no natural boundary, since at any geographical point a particular language is undergoing some change.

At best, they are defined by 'waves of innovation'—in other words, areas where some set of innovations converge and overlap. The 'wave' concept is integral to Saussure's model of geographical linguistics—it describes the gradient manner in which dialects develop. Linguistic waves, according to Saussure, are influenced by two opposed forces: parochialism, which is the basic tendency of a population to preserve its language's traditions; and intercourse, in which communication between people of different areas necessitates the need for cross-language compromise and standardization. Intercourse can prevent dialectical fragmentation by suppressing linguistic innovations; it can also propagate innovations throughout an area encompassing different populations. Either way, the ultimate effect of intercourse is unification of languages. Saussure remarks that there is no barrier to intercourse where only gradual linguistic transitions occur. Having outlined this monoglot model of linguistic diversity, which illustrates that languages in any one area are undergoing perpetual and nonuniform variation, Saussure turns to languages developing in two separate areas.

In the case of segregated development, Saussure draws a distinction between cases of contact and cases of isolation. In the latter, commonalities may initially exist, but any new features developed will not be propagated between the two languages. Nevertheless, differentiation will continue in each area, leading to the formation of distinct linguistic branches within a particular family.

The relations characterizing languages in contact are in stark contrast to the relations of languages in isolation. Here, commonalities and differences continually propagate to one another—thus, even those languages that are not part of the same family will manage to develop. Criticism See.

Editions There have been two translations into English, one by (1959), and one by (1983). Saussure, Ferdinand de. Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court. 1983 See also. Notes.

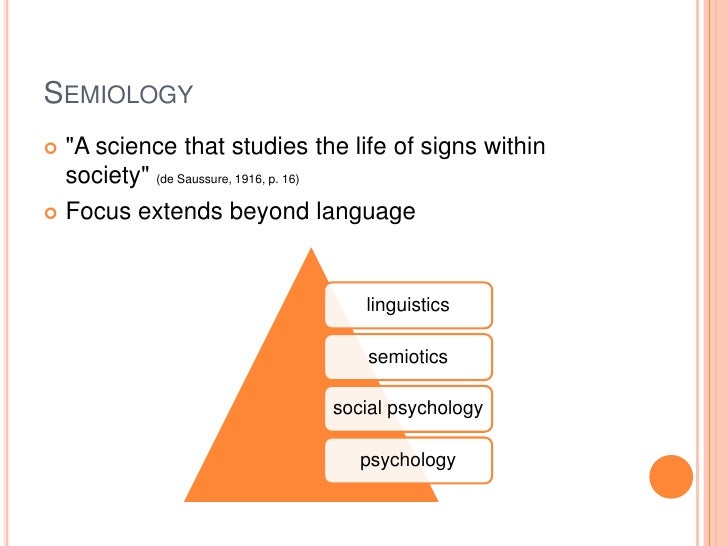

This new edition of Ferdinand de Saussure's Course in General Linguistics (1916) is the first critical edition of Saussure to appear in English. It also restores Wade Baskin's delightful original English translation (1959), which has long been unavailable. The founder of modern linguistics, Saussure inaugurated semiology, structuralism, and deconstruction and made possible the work of Jacques Lacan, French feminism, cultural studies, New Historicism, and postcolonialism. Based on the lectures that Saussure gave at the end of his life at the University of Geneva, the text of the Course was collated from notes taken by Saussure's students and published by Charles Bally, Albert Sechehaye, and Albert Riedlinger. Saussure traces the rise and fall of the historical linguistics in which he was trained, the synchronic or structural linguistics with which he replaces it, and the new look of diachronic linguistics subsequent to this change in scholarly perspective. Most important, Saussure presents the general principles of a new linguistic science which includes among its achievements the invention of semiology: the theory of the 'signifier,' the 'signified,' and the 'sign' which they combine to produce. Relaunching Baskin's translation restores these terms and makes Saussure's thought once again clear and accessible.

Baskin's translation allows readers to experience how Saussure shifts the theory of reference from mimesis to performance and expands the purview of poetics to include all media, including life sciences and environmentalism. The introduction to this new edition situates Saussure's position in the history of ideas and describes the history of scholarship that made the Course in General Linguistics legendary. New endnotes enlarge Saussure's contexts well beyond linguistics to include literary criticism, cultural studies, and philosophy. Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) received his doctorate from the University of Leipzig in 1880 and lectured on ancient and modern languages in Paris until 1891. He then taught Sanskrit and Indo-European languages at the University of Geneva until the end of his life.

Among his published works is Memoir on the Primitive System of Vowels in Indo-European Languages, published in 1878 when Saussure was twenty-one.Wade Baskin (1924-1974) was a professor of languages at Southeastern Oklahoma State University and translated many works from French, including books by Jean-Paul Sartre.Perry Meisel is professor of English at New York University. His books include The Myth of the Modern, The Literary Freud, and The Myth of Popular Culture.Haun Saussy is university professor in the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of Chicago. His books include The Problem of a Chinese Aesthetic and Great Walls of Discourse.