Davide Bonetti wrote on Sat, 07 January 2006 18:22 Visio can only make blocks, as previously stated. Whatever gave you the idea that Visio can only draw blocks? Serials, numbers and keys for Serial Number Project Xto7. Make your Software full version with serials from SerialBay. Project Crack, project Keygen, project Serial, project No Cd, project Free Full Version Direct. Found 7 results for Xto7. Full version downloads available, all hosted on high speed servers! Download servers online: 7.

Released a plugin in the App store that converts FCP X projects to FCP 7 sequences. ($49.99), previously named Project Xto7, translates the FCP X Project XML (fcpxml) and converts it for import into Final Cut Pro 7. You can also go directly to Color, Soundtrack Pro, and to other Final Cut Pro 7 XML workflow programs, as well as to Adobe Premiere Pro (and thus to After Effects via dynamic link). For a full explanation of the capabilities of Xto7 for Final Cut Pro, go to and download the. (Assisted Editing is the joint venture of Phillip Hodgetts and Gregory Clarke.) From Assisted Editing’s Xto7 Support Resources: To use Xto7. In FCP X, select the project you want to send to FCP 7 in the Project Library.

(Do not open the timeline—just select the project in the Project Library. (If you have Final Cut Pro X and Final Cut Pro 7 installed on different Macs or partitions, make sure the Project and its referenced Events are on an external storage device.). Choose the File menu and select Export XML, and name and save the FCPXML file. (If Final Cut Pro X and Final Cut Pro 7 are installed on different Macs or partitions, save the FCPXML file to the Project’s external storage device.). To translate the Project to a Final Cut Pro 7 sequence, either:. Run Xto7 for Final Cut Pro and use the open dialog to locate your exported FCPXML file (the open dialog allows you to select more than one FCPXML file);. Drag-and-drop the FCPXML file onto the Xto7 for Final Cut Pro application icon;.

Right-click on the FCPXML file in Finder and choose Open With Xto7 for Final Cut Pro from the contextual menu. A progress bar appears.

When finished, you will be asked if you want to Send to Final Cut Pro 7 or Save Sequence XML. Choose Send to Final Cut Pro 7 and click OK. Final Cut Pro 7 will launch and display an Import XML dialog. Use the Destination popup menu to choose whether to create a new project or add the sequence to an open project. If the Sequence Settings popup menu is set to (auto) the sequence will use the Audio Channels, Audio Sample Rate and Render Format of the Final Cut Pro X project; or you can choose your own setting for the new sequence (this can be changed later).

Turn on the Reconnect to Media Files, Include Markers and Include Audio/Video Effects checkboxes. Click OK to import the new sequence. Product Reviews Be sure to download the for additional resources and “Known Issues” about this conversion process.

Is steadily gaining numbers among professional editors as Apple integrates more features in response to users’ needs. Unlike the previous iterations of Final Cut Studio – where everything was integrated into a bundle of Apple applications – FCP X relies more on an ecosystem of outside developers who have brought a number of useful tools to the table. This means that you only buy what you need and fill your toolkit according to your own specific workflow. Here are some tips on getting the most out of the FCP X.

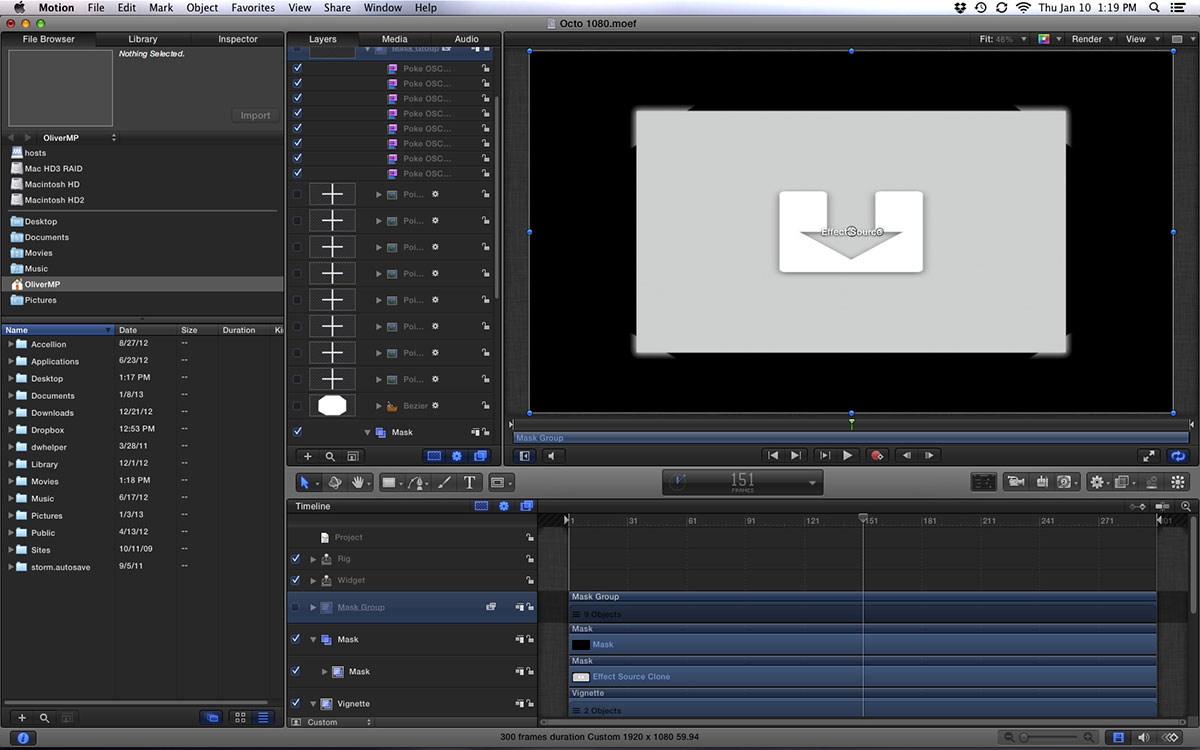

( Click on images for an expanded view.) Motion and Compressor Apple sells and as standalone applications through the Mac App Store. Although not essential for running FCP X, each adds useful functions. Motion 5 is an advanced compositor that’s optimized for the design and animation of motion graphics. It also has become an effects creation tool for Final Cut Pro X. Many of the filters, transitions and generators found in FCP X are actually Motion templates. It’s easy to open a copy of an effect from FCP X into Motion and customize it. Likewise, you can create you own effects plug-ins from scratch and “publish” them back to Final Cut.

Many of the free or low-cost filters available for FCP X were created exactly this way. Compressor 4 is an updated version of Apple’s encoding software. This new version is faster and better optimized for current hardware and includes new presets for Apple devices. Since DVD and Blu-ray creation has been integrated into the FCP X Share menu, as well as Compressor, this will be the tool you need for separate production of “one-off” review discs. Moving between the Final Cuts Final Cut Pro X introduced a new version of XML, which differs greatly from the XML used by Final Cut Pro 7 or Adobe Premiere Pro.

Yet, this the core method Apple provides for interchange with other applications. If you need AAFs, OMFs, FCP 7 XMLs, EDLs and so on, you first have to go through the new FCPXML format. To date, only a handful of applications, like DaVinci Resolve, can natively read/write FCPXML; therefore, general interoperability will require one of several third-party translation utilities. / jumped into the game early with applications designed to make FCP X a better citizen of the post world.

Xto7 for Final Cut Pro and 7toX for Final Cut Pro are XML translation utilities that let editors bring legacy FCP projects into FCP X, as well as to go from FCP X back to FCP 7 (or Premiere Pro). Although the need for 7toX seems obvious, going in the other direction (Xto7) is also quite useful. For instance, it’s the only efficient way to create an audio OMF from an FCP X project. Use the translation to get the timeline into FCP 7, where you can generate the OMF export.

This is also a good way to get from FCP X to Apple Color, if that’s still your preferred grading application. Other applications for FCP X from Intelligent Assistance include Sync-N-Link X. It is designed to batch-process double-system audio synchronizing based on timecode. Lastly Event Manager X is a tool for editors to control which Events and Projects show up inside Final Cut Pro X at launch. Interoperability with other applications Apple left EDL generation to third-party developers. Is the application to use if you need to generate CMX 3600-compliant edit decision lists (EDLs).

This is still an important need in many industry workflows, such as sending files and a sequence to an outside color correction or visual effects facility. EDL-X gives you control over customizing lists based on the needs at the other end. This includes length of reel names, which data is used for the reel names and the inclusion of source lists. Final Cut Pro X uses a trackless timeline design, which doesn’t translate to a layout required by audio mixers working on a DAW, like Avid Pro Tools. The software designed to translate an FCP X Project (edited sequence) for Pro Tools use is.

It reads the FCPXML file and generates an AAF file with linked or embedded media. This is compatible with newer versions of Pro Tools. In addition, the FCP X Roles and Sub-roles feature is used to organize the track layout when the file is opened in a Pro Tools session. What if you want to mix the audio yourself, but don’t own Pro Tools? There’s another option.

Assuming that Soundtrack Pro is installed on your computer (part of the “legacy” Final Cut Studio) or you’ve purchased Adobe Production Premium CS6, which includes Audition, then you can also use Xto7 to translate your timeline’s audio into XML. Import the translated XML list into one of these DAW applications, which will automatically link to the audio files on your hard drives. Now you can mix the audio in a familiar track-based environment. If you’ve left Apple Color behind, then is tailor-made for Final Cut Pro X. The roundtrip between the two applications is solid and even their user interfaces sport similar aesthetics.

Resolve is a world class grading tool used on blockbuster features, but even the free version will cover nearly all of your needs. Another interesting free (donation requested) application is.

This translation utility can generate composition files for SynthEyes, Nuke and After Effects from FCP X timelines, as well as self-contained or reference QuickTime movies from individual Event clips. Two more applications that will add powerful capabilities to your system are and. PluralEyes 3 is a standalone application for clip synchronization using audio. It can sync double-system productions, as well as multiple camera angles based on matching audio waveforms, without the use of timecode. This new version supports the FCPXML format, as well as roundtrips to and from FCP X.

Soundbite is a dialogue search engine powered by Nexidia and used to be known as Get before Boris FX picked up the product. It’s the cousin of Avid’s PhraseFind, but operates outside of any specific NLE. To use it with FCP X, first analyze a folder of media to search for specific words, phrases or terms. Markers are placed at the word matches within the “found” clips. Then generate an FCPXML file for these search results, which will be imported into Final Cut as a new Event, complete with markers placed at the locations of the word matches. Finally, let’s not for get the useful workflow and maintenance/system management tools from, like and. Filters, transitions, titles, generators and templates Video effects in Final Cut Pro X are based on Motion templates built on an updated version of the FxPlug architecture.

Many of the effects created for FCP X by third-party developers are simply a combination of native Motion effects, which have been “published” as a single FCP X effect. In this process, the developer can choose to limit or reveal as many adjustment sliders as is appropriate. Therefore, a very complex effect can be controlled with a single slider within the FCP X inspector pane. Love hina episode 17. Some plug-in developers go beyond that, of course, but the combination of the traditional developers and the new crop of editor-designer-entrepreneurs has led to a rich ecosystem of effects just for FCP X. All of the major developers have introduced FCP X products. These include, and many more.

I find those from and to be the best match for most users. Digital Heaven’s, effects form a nice combination of tools that you’ll use every day.

Not overly flashy, but very useful. Noise Industries’ FxFactory is the only comprehensive package that you can grow as your need increases. The free version acts as a license manager for the partner plug-ins, while the paid Pro version adds a set of Noise Industries’ own filters. Most of these plug-ins run in FCP 7/X, After Effects and Premiere Pro, although a few are specific to only FCP X. Since these plug-ins are developed by individual partner companies, like and others, you can buy the filters as you need them and grow the repertoire over time.

Final Cut Pro X naturally includes a nice complement of built-in filters, so before you started draining the bank account, you should definitely check out what’s already included. If you want freebees based on Motion templates, simply scour the web for a plethora of effects. And the filters are a good starting point. FCP X also includes a wide range of audio filters brought over from. It also recognizes most third-party AU (Mac audio units) filters, like or plug-ins. Apple Final Cut Pro X is proving to be a viable platform for the professional user.

You’ll find a range of tools that augment FCP X, which will enable you to complete productions at nearly any level of complexity. The supporting ecosystem of applications, utilities and plug-ins is growing every day and quickly expanding this next generation Final Cut Pro beyond it seemingly simple beginning. ©2013 Oliver Peters. Peter Jackson’s was one of the most anticipated films of 2012. It broke new technological boundaries and presented many creative challenges to its editor. After working as a television editor, started his own odyssey with Jackson in 2000 as an assistant editor and operator on The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

After assisting again on King Kong, he next cut Jackson’s Lovely Bones as the first feature film on which he was the sole editor. The director tapped Olssen again for The Hobbit trilogy, where unlike the Rings trilogy, he will be the sole editor on all three films. Much like the Rings films, all production for the three Hobbit films was shoot in a single eighteen month stretch. Jackson employed as many as 60 RED Digital Cinema EPIC cameras rigged for stereoscopic acquisition at 48fps – double the standard rate of traditional feature photography. Olssen was editing the first film in parallel with the principal photography phase. He had a very tight schedule that only allowed about five months after the production wrapped to lock the cut and get the film ready for release.

To get The Hobbit out on such an aggressive schedule, Olssen leaned hard on a post production infrastructure built around Avid’s technology, including 13 Media Composers (10 with Nitris DX hardware) and an ISIS 7000 with 128TB of storage. Peter Jackson’s production facilities are located in Wellington, New Zealand, where active fibre channel connections tie, and the cutting rooms to the Avid ISIS storage. The three films combined, total 2200 hours (1100 x two eyes) of footage, which is the equivalent of 24 million feet of film. In addition, an Apace active backup solution with 72TB of storage was also installed, which could immediately switch over if ISIS failed. The editorial team – headed up by first assistant editor Dan Best – consisted of eight assistant editors, including three visual effects editors.

According to Olssen, “We mimicked a similar pipeline to a film project. Think of the RED camera.r3d media files as a digital negative. Peter’s facility, Park Road Post Production, functioned as the digital lab. They took the RED media from the set and generated one-light, color-corrected dailies for the editors. 24fps 2D DNxHD36 files were created by dropping every second frame from the files of one ‘eye’ of a stereo recording.

For example, we used 24fps timecode with the difference between the 48fps frames being a period instead of a colon. Frame A would be 11.22.21.13 and frame B would be 11:22:21:13. This was a very natural solution for editing and a lot like working with single-field media files on interlaced television projects.

The DNxHD files were then delivered to the assistant editors, who synced, subclipped and organized clips into the Avid projects. Since we were all on ISIS shared storage, once they were done, I could access the bins and the footage was ready to edit, even if I were on set. For me, working with RED files was no different than a standard film production.” Olssen continued, “A big change for the team since the Rings movies is that the Avid systems have become more portable. Plus the fibre channel connection to ISIS allows us to run much longer distances.

This enabled me to have a mobile cart on the set with a portable Media Composer system connected to the ISIS storage in the main editing building. In addition, we also had a camper van outfitted as a more comfortable mobile editing room with its own Media Composer; we called it the EMC – ‘Editorial Mobile Command’. So, I could cut on set while Peter was shooting, using the cart and, as needed, use the EMC for some quick screening of edits during a break in production. I was also on location around New Zealand for three months and during that time I cut on a laptop with mirrored media on external drives.” The main editing room was set up with a full-blown Nitris DX system connected to a 103” plasma screen for Jackson. The original plan was to cut in 2D and then periodically consolidate scenes to conform a stereo version for screening in the Media Composer suite. Instead they took a different approach. Olssen explained, “We didn’t have enough storage to have all three films’ worth of footage loaded as stereo media, but Peter was comfortable cutting the film in 2D.

This was equally important, since more theaters displayed this version of the film. Every few weeks, Park Road Post Production would conform a 48fps stereo version so we could screen the cut. They used an, because it could handle the frame rate and had very good stereo adjustment tools. Although you often have to tweak the cuts after you see the film in a stereo screening, I found we had to do far less of that than I’d expected. We were cognizant of stereo-related concerns during editing. It also helped that we could judge a cut straight from the Avid on the 103” plasma, instead of relying on a small TV screen.” The editorial team was working with what amounted to 24fps high-definition proxy files for stereo 48fps RED.r3d camera masters.

Edit decision lists were shared with Weta Digital and Park Road Post Production for visual effects, conform and digital intermediate color correction/finishing at a 2K resolution. Based on these EDLs, each unit would retrieve the specific footage needed from the camera masters, which had been archived onto LTO data tape. The Hobbit trilogy is a heavy visual effects production, which had Olssen tapping into the Media Composer toolkit. Olssen said, “We started with a lot of low resolution, pre-visualization animations as placeholders for the effects shots.

As the real effects started coming in, we would replace the pre-vis footage with the correct effects shots. With the Gollum scenes we were lucky enough to have Andy Serkis in the actual live action footage from set, so they were easy to visualize how the scene would look. But other CG characters, like Azog, were captured separately on a Performance Capture stage. That meant we had to layer separately-shot material into a single shot. We were cutting vertically in the timeline, as well as horizontally. In the early stages, many of the scenes were a patchwork of live action and pre-vis, so I used PIP effects to overlay elements to determine the scene timing. Naturally, I had to do a lot of temp green-screen composites.

The dwarves are full-size actors and for many of the scenes, we had to scale them down and reposition them in the shot so we could see how the shots were coming together.” As with most feature film editors, Jabez Olssen likes to fill out his cut with temporary sound effects and music, so that in-progress screenings feel like a complete film. He continued, “We were lucky to use some of Howard Shore’s music from the Rings films for character themes that tie The Hobbit back into The Lord of the Rings. He wrote some nice ‘Hobbity’ music for those. We couldn’t use too much of it, though, because it was so familiar to us!

The sound department at Park Road Post Production uses Avid Pro Tools systems. They also have a Media Composer connected to the same ISIS storage, which enabled the sound editors to screen the cut there. From it, they generated QuickTime files for picture reference and audio files so the sound editors could work locally on their own Pro Tools workstations.” Audiences are looking forward to the next two films in the series, which means the adventure continues for Jabez Olssen. On such a long term production many editors would be reluctant to update software, but not this time.

Olssen concluded, “I actually like to upgrade, because I look forward to the new features. Although, I usually wait a few weeks until everyone knows it’s safe. Other nonlinear editing software packages are more designed for one-man bands, but Media Composer is really the only software that works for a huge visual effects film. You can’t underestimate how valuable it is to have all of the assistant editors be able to open the same projects and bins. The stability and reliability is the best.

It means that we can deliver challenging films like The Hobbit trilogy on a tight post production schedule and know the system won’t let us down.” ©2013 Oliver Peters Posted in, Tagged,. This past Monday at, Adobe clarified its plans going forward. Gone is the “next” label, as well as any mention of “Creative Suite 7”. Premiere Pro, Photoshop, et al, become Premiere Pro CC, Photoshop CC and so on.

With a few exceptions, like Lightroom, perpetual licenses (where you “own” the software) are gone. Clearly Adobe was having its own “FCP X moment”. ( warning: offensive language). Before I continue, here are links to and official responses/clarifications from, and in various forums, so you have the straight scoop.

Although we tend to think of software ownership like any other asset, digital media plays by a different set of rules. What you own is a license to use the software freely according to the terms of the EULA. It’s not an asset that you can use in an unrestricted manner, such as unlimited installation or resale on the open market. In fact, in the “bad ole” Avid days of turnkey systems, you actually had to pay a transfer fee when selling a system to another user. This was often waived, but did nothing to endear users to Avid. Even today, you typically cannot legally sell used (already registered) software to others in the same way that you sell used computers – although people do it every day without issue.

The bottom line is that you may have application files on your drives or installation DVD-ROMs, but you don’t own these in the same way you own a physical, printed book – or a printer. Clearly the concept of “ownership” is limited in the digital world, but at least what we understand as “owning” is completely different than renting. Essentially that’s the shift Adobe has made. If you buy a monthly or annual Creative Cloud subscription (or a single-application subscription), then you are renting the software covered under that agreement.

The term “cloud” is a bit misleading, since the application software is downloaded and resides on your local computer, just like any other software. The software is authorized over the internet and it pings Adobe’s license servers monthly to see if you’ve paid your bill. This is more or less like the cable company, which installs a set-top receiver/DVR box in your house, though you don’t own that hardware. With Adobe, this shifts your use of the software from a capital outlay to a monthly expense, like other services or utilities costs. If you quit your CC subscription, your software is de-authorized and you lose the ability to use it or even open existing project files. The software can stay on your computer and you can renew the subscription at some point down the road if you like. This model has several benefits for Adobe, such as a constant and somewhat predictable revenue stream.

Since the software is now a service, it gets them out of some of the legal issues revolving around the release of features and timing of new products coming to market. In essence, Adobe never has a “new product”, but rather posts updates to the Cloud, that users can download when they want or need to. Their claim is that new features can be introduced more quickly, because the aren’t bound by the “features versus bug fixes” conundrum that’s become an unintended consequence of SOX. I’m skeptical of these claims, since most downloaded software over the past few years has enjoyed reasonably rapid development between big point releases.

You can only develop new software so quickly and having a different delivery vehicle may or may not improve that. The ultimate question, though, is whether or not this is good for the user of Adobe products. Clearly the Creative Cloud change is one that benefits enterprise customers – the largest post houses, corporate media departments, digital media-centric ad agencies, broadcasters and TV/cable networks. These are customers who are more comfortable with a monthly fee system.

They may already pay support contracts and want frequent updates. Their media is often perishable, so opening legacy projects might not be a concern. Adobe has also sweetened the pot with additional CC services and storage. If you are an individual Adobe power user – meaning you’ve used many if not all of the applications in a Master Collection or Production Premium bundle – and you update annually anyway – then the Creative Cloud subscription will likely save you money. However, if you only use one or two applications and update only every few years, then a subscription just increased your costs.

I see plenty of users who don’t upgrade. For example, at freelance sites, I routinely run into a range of CS4 through CS5.5 products. These users are quite happy with After Effects or Photoshop in those versions. Historically Adobe has not given all apps within a bundle equal treatment. For instance, in one version After Effects may get a few whizz-bang features, while Premiere Pro only gets a few tweaks.

The next time, it’s the other way around. So the subscription model is only of benefit if Adobe updates and you actually need those updates.

Often software updates require newer hardware to take advantage of the next features or performance. Users may or may not be ready to bump up their hardware or their OS versions.

Adobe will have older versions available on the Cloud, so you don’t necessarily have to run the newest software. If that’s the case, though, then what is the benefit to you of the subscription if you are not going to use the latest software? There currently are four basic software use/own/rent models: Perpetual License – This is paid “ownership” as discussed above.

Avid, Grass Valley and others follow this model. Sometimes it comes with an optional support contract.

Software as a Service – This is the concept of the Adobe Creative Cloud. They aren’t the only one. Look to Intuit, Microsoft, Google and others for similar models and it will increasingly be the way a lot of software companies go.

Mac App Store – This is Apple’s approach and specifically applies to Final Cut Pro X, Aperture and other Apple and third-party software. You buy the software one time. The most current version is the one always available at the MAS and you can download and update for free when you are ready. As long as the product is sold as the same product, the developer cannot charge for an update. If the product changes or is rebranded, it can be sold (at full price) as a new application.

You can install the software (for a single application charge). Professional use is intended as. Free with “strings” – This would apply to DaVinci Resolve and Lightworks. The basic model is free, but the developer offers certain value-added options or “add-ons”.

Examples include the Lightworks Pro package (subscription to cover licensed codec support) and Blackmagic Design’s restriction of Resolve to working with its own hardware i/o products. I’m a fan of most of Adobe’s products. Although I’m a relatively knowledgeable user of these tools, I am by no means a “power user” of Photoshop or After Effects, though I’m comfortable working there. As a magazine and blog reviewer of software, I have evaluation copies of the various Creative Suite Master Collections from over the years and for the most part, I have never touched many of the print, web or Flash applications.

I am also well aware of how capricious some software decisions can be. For example, for a few years, Adobe was developing Soundbooth – a streamlined, task-oriented audio application. It included a proprietary music tailoring function (like Smart Sound’s Sonicfire), using Adobe’s own scores.

A few were included and then you could buy more scores to augment your library. I bought a number of these. Then Adobe decided Soundbooth wasn’t working for them and not enough folks were purchasing the additional scores.

So they killed the product and dumped the scores out as a free download (including those I had paid for a year earlier). Unfortunately Audition (which replaced Soundbooth in the bundles), no longer has any ability to use these scores. In fact, nothing except Soundbooth can. A few months ago I had to re-install Soundbooth from CS4 or CS5 on my MacBook Pro just to be able to build some tracks using these scores.

The point is that there’s no reason that Adobe wouldn’t decide to dump some app in the future, like Prelude or SpeedGrade, for instance. After all, they can now track specific application downloads and can tell what people are using.

No more bundles to shield the unproductive. Of course, Adobe has stated that if that were the case in the future, they would simply make the EOL’ed product available for download and use without further authorization to existing customers. I don’t want any of this to sound like Adobe is doing something evil.

They aren’t and I feel that companies have to do what makes the most sense for their survival and continued product development. I think the negative reaction could have been blunted if Adobe had included an “opt-out/buy-out” mechanism. For example, if you’ve subscribed for a year and don’t want to continue, you could buy a perpetual license to the software you have on a prorated basis.

That would be a win-win in my book. I personally prefer the perpetual license model or the Mac App Store. I think there’s a real issue for smaller production companies and individuals with the “monthly cost creep” that this all amounts to. It’s not just Adobe. Factor in your cable bill, your phone data plan and other services like Vimeo, Dropbox and more. These all start to add up to real dollars that run the risk of “nickel and diming” a small business to death. My druthers are the Apple Mac App Store model for know.

It is the most cost-effective. I also don’t believe that all of Adobe’s applications are “best in class”. Photoshop and After Effects probably are, but others – not so much. I don’t understand the need for Prelude, other than to fill in gaps that Premiere Pro is missing – like transcoding. Photoshop is pretty bloated for the casual user and long ago needed something between it and Photoshop Elements.

My point is that for a user like me, the full Creative Cloud model doesn’t look too appealing. There are viable alternatives to all of Adobe’s solutions, but if you need to maintain compatibility with client-supplied Adobe files, you will likely find it hard to get by without some Adobe product. My suggestion for most users in similar shoes would be. This gives you a fallback position. Then if you want to move forward with the Cloud, run the numbers. If you are a power user of Photoshop, Premiere Pro or After Effects and want to have the latest version of that one application, simply buy a single-application subscription.

If you use three or more applications on a regular basis and want those all to be current, then the full Creative Cloud subscription makes sense. You still have the CS6 versions if needed, as long as you’ve maintained backwards project compatibility.

The last thought I’ll leave you with is this. Adobe’s applications are built around web services. For now, these are locally-installed applications; but, they could also function as the front end user interface for software that actually does reside at a remote location (“the cloud” for real). That’s the concept behind Adobe Anywhere. In short, could the “end game” be for a strictly cloud-based, software as a service operation? Adobe Creative Cloud running like Google Docs? Maybe – maybe not.

EDIT: Since I posted this entry, I’ve received some feedback from my friends at Adobe. If you are an enterprise user with a Creative Cloud Team subscription, there’s even more value, such as a larger amount of storage. While some of these features might not be needed if you already are using Dropbox, Vimeo or a WordPress blog as your website, the Cloud subscription does put these types of resources under one roof. An enterprise customer, such as a broadcast station group, may well find the Creative Cloud plans quite attractive. They can negotiate deals that place Adobe apps on any computer within their creative departments across all divisions of the company. This type of customer really isn’t too worried about opening legacy projects from a few years ago. By shifting software purchasing to the monthly expense part of the ledger, it removes it from the annual capital expenditure battles and guarantees more frequent updates across departments.

So, while there is a lot of back and forth comment across the internet about Adobe’s move, I should note that quite a few customers are and will be very happy climbing into the Cloud. ©2013 Oliver Peters Posted in Tagged.

Autodesk attracted a lot of attention last year with the revamped version of. I had originally been working on a review with the earlier version (Smoke 2012), but held off when I found out Smoke 2013 was just around the corner. Indeed, the more “Mac-like” refresh wowed NAB attendees, but it took until December to come to market. In that time, Autodesk built on the input received from users who tested it during this lengthy public beta period. Now that it’s finally out in the wild, I’ve had a chance to work with the release version, both on my own system, as well as at a client site where Smoke 2013 has been deployed.

Both of these are on recent model Mac Pros. Although Smoke 2013 is a very deep application, I would offer that the learning curve for this new version is a mere 25% of what it used to be. That’s a significant improvement. Getting set up There are several ways to install and operate Smoke 2013.

Most users will install the application in the standalone mode. The software is activated over the internet and works only on that licensed machine.

Facility users can also purchase license server software, which allows them to float the Smoke license among several machines. Only one at a time is activated, but any of the machines can run the software, based on the permission assigned by the license server application over the internal LAN. Smoke 2013 operation is tied to the media storage, so the first thing to do after software installation is to run the Smoke set-up utility. This allocates which drives are accessible to Smoke. You can grab media files from any connected drive, but specific locations must be assigned as library locations for media caches, proxies, render files and so on. These can be internal drives, SAN volumes or externally-connected drives. The key is that when you create or launch a project, it is tied to a specific library location.

If that drive is unmounted, any projects associated with it won’t show up and are not accessible (even in an offline mode) to the operator. You should approach Smoke operation with a media strategy in mind.

Project Xto7 Keygen Mac Free

Smoke 2013 handles more native codecs and file formats – and in a more straightforward fashion – than Smoke 2012. If you are working with ProRes media, for instance, no conversion is necessary to get started in Smoke and files can be rendered as ProResHQ, instead of the previous default of uncompressed DPX files. This means drive performance requirements are less than in the past, but it’s still a good idea to use fast RAID arrays. Even two 7200RPM SATA drives striped as RAID-0 will give you acceptable performance with ProRes media. Naturally, a faster array is even better. Smoke will let you render intermediate proxies for even better performance, but if you want to simply drag in new media from the Mac Finder, then Smoke 2013 now performs on par with other desktop NLEs.

Smoke uses OpenGL and not CUDA or OpenCL acceleration, so performance from ATI or NVIDIA cards is on even footing. If you run a dual monitor system, like my set-up with two 20” Apple Cinema Displays, you can enable dual-screen preview. This will let you mirror the UI or display a selected viewport, which is most often the current clip, but can also be the ConnectFX schematic. You are best off with two 1920×1080 or 1920×1200 screens. The scaling function to reduce the full screen viewer to fit my 1680×1050 resolution introduced artifacts and affected the performance of the card. Smoke 2013 can work with screen resolutions starting at 1440×900, but it’s better to stick to one higher resolution screen like a single 27” or 30” Apple Cinema Display or iMac screen.

It’s best to run a broadcast monitor connected to an AJA KONA, IoXT or Blackmagic Design card (in a future version). In that configuration, you can’t use a second computer display to extend the real estate of the Smoke user interface, but could display the UI from another open application, like Adobe Photoshop. The editing experience The reaction to Apple Final Cut Pro X kicked up interest in Smoke. Users who wanted a 64-bit, track-based application that didn’t stray too far from FCP 7’s operational style, felt that Smoke 2013 might be the hypothetical “FCP 8”.

Autodesk indeed sports an editing workspace that is closely aligned with the look and feel of Final Cut Pro “legacy”, as well as Adobe Premiere Pro. It even defaults to FCP 7 keyboard shortcut commands. If you can edit on Final Cut (before FCP X) or Premiere Pro, then you can be productive on Smoke with little relearning. The user interface is divided into three panes – a browser, a viewing area and a workspace. Across the bottom are four tabbed interface pages or modes – MediaHub, Conform, Timeline and Tools. MediaHub is where you search drive locations for files.

It is analogous to Adobe’s Media Browser within Premiere Pro. Locate files and drag or import them into the editing browser window. Conform lets you reconcile imported media with edit lists and is also a place to relink media files. Timeline is the standard editing workspace and lastly, Tools holds clip tools and utilities, such as deinterlacing, pulldown, etc. Each pane changes the information displayed, based on the context of that mode.

In the Timeline mode, you see viewers and a timeline, but in the MediaHub mode each pane shows completely different information. Editors will spend most of their day in the Timeline mode.

This interface page is organized into the standard editing view with player windows at the top and a track-based timeline at the bottom. Smoke always loads at least two timelines – the edited sequence and the selected source clip. Effects can be applied to the source clip, as well as to clips on the timeline.

The viewer pane can display clips on a single, toggled viewer (like FCP X) or traditional source/record windows (like FCP 7). There’s also a thumbnail and a triptych view.

The latter is helpful during color correction, if you want to display previous/current/next frames for shot matching. The browser displays all imported source clips for a project. It can be placed on the left, on the right or hidden entirely. Within it, clips can be organized into folders. You may have more than one sequence in a project, but only one project can be open at a time. As you select a clip, it immediately loads into the viewer and timeline window.

No double-clicking required. Smoke is a good, fast editor when it comes to making edits and adjusting clips on the timeline. There are some nice touches overlooked on other NLEs. For example, it uses track-based audio editing with keyframable real-time mixing. There are a set of audio filters that can be applied and the output has a built-in limiter.

Formatting for deliverables is built into the export presets, so exporting a 1080p/23.976 sequence as 720p is as simple as picking a preset. The edit commands include the standard insert, overwrite and replace functions, but also some newer ones, like append and prepend. Ripple and snapping are simple on/off toggles. While editing is solid, I would still categorize Smoke 2013 as a finishing tool.

You could edit a long-form project from scratch in Smoke, but you certainly wouldn’t want to. It lacks the control needed for narrative long-form, like detailed custom bin columns, a trim tool, multi-camera editing and more. On the other hand, a scripted short-form project, like a TV commercial – especially one requiring Smoke’s visual effects tools – could be edited exclusively within Smoke.

The better approach is to do your rough cuts in another desktop NLE and then send it to Smoke for the remainder. You can import various edit list formats – EDL, XML, FCPXML and AAF.

Cut on Final Cut Pro 7/X, Premiere Pro or Media Composer and export an edit decision list in one of these formats for the sequence. Then import and link files in Smoke and you are ready to go. In my testing, XMLs from both FCP 7 and FCP X worked really well, but AAFs from Media Composer were problematic.

Typically Smoke had difficulty in relinking media files when it was an Avid project, most likely due to issues in the AAF. Come for the effects The visual effects tools are the big reason most editors would use Smoke 2013 over another NLE. There are four ways to apply effects.

The first and easiest is the effects “ribbon” that flies out between the viewers and the timeline. It contains eight standard effects groups – Timewarp, Resize, Text, Color Correction, Spark, Blend, Wipe and Axis. (Spark is the API for third party filters. GenArts Sapphire is the first effects package for Smoke 2013.) The “ribbon” effects are always applied in the same order and some are multiple purpose tools. For instance, the Resize effect is automatically applied for format correction, such as a ProRes4444 clip in a ProResHQ timeline. When these effects are added to a clip on the timeline, a reduced set of parameters appears in a fly-out panel at the top of the timeline. You can immediately apply and adjust effects in the timeline without the need to step deeper until you’ve mastered the simpler methods.

The last effect, Axis, is a “super tool”. It’s the 2.5/3D DVE effect, but you can enter its effects editor and do a whole lot more. Axis lets you add text, lighting, 3D cameras, plus adjust surface properties and surface deformations. Once you enter any of the effects editors, the mode changes and you are in a new user interface specific to the context of that effect. The controls flow left to right and change options according to the selections made.

For instance, picking “object” within the Axis effect editor gives you controls to adjust the scale, position and rotation of the clip. Pick “lights” and the control parameters change to those appropriate for lighting.

The third way to build an effect is to select ConnectFX. This brings you into Smoke’s world of node-based composting, where you are presented with a flow chart schematic, a viewer and a set of filter tools.

An effect like Color Correction may be applied directly to the timeline as a single filter or as a filter within a ConnectFX build. It’s entirely up to the comfort level of the editor and how many additional effects will be applied to that clip for the final look. One of available tools within the set is Action, which is a separate compositing method. It forms the fourth way to build effects. You can composite multiple media clips in an Action node, such as a title over a background.

Once you step into an Action node, you are presented with its own schematic. Instead of a flowchart, the Action schematic shows parent-child links between layers of the composite, such as a light that is attached to a media clip. Action is where you would make adjustments in 3D camera space.

Some tools, like the 3D lens flare effect are only available in Action. Smoke detractors make a big deal out of the need to render everything.

While this is true, I found that a single effect applied from the FX “ribbon” menu to a clip on the timeline will play in real time. If you’ve applied more than one effect to a clip, then usually the last one in this string will be displayed live during playback. When rendering is required, the processing speed is pretty quick. If you export a sequence with unrendered effects, then all effects are first processed (rendered) before the finished, flattened master file is exported. Conclusion Smoke 2013 is likely to be one of the deepest, but powerful, editing applications you will ever encounter. It’s deceptively simple to start, but takes a concentrated effort to master the inner workings of its integrated, node-based compositors. Nevertheless, you can start to be productive without having to tackle those until you are ready.

In an editing world that’s gravitating towards an ever-growing number of canned, one-button preset effects, Smoke 2013 unabashedly gives you the building blocks needed for that last 5% of finesse, not available from a preset effect. You can even build your own complex presets to be applied on future projects. That takes time and talent to master. Fortunately Autodesk has gone the extra mile with good tutorials available on their and the. Smoke is ideal as a finishing tool in a multi-suite facility, the main system in a creative media shop or the go-to system for broadcast promotion production. It is designed to fulfill the “hero” role and is targeted squarely at the Adobe suite of tools. The sales pitch is to stay within Smoke’s integrated environment rather than bounce among several applications.

While Smoke 2013 largely meets that objective, it still gets down to personal preferences – compositing in nodes versus a track-based tool like After Effects. Installation is easier than it was, but I’d still like to see Autodesk improve on the activation process – especially for those interested in using more than one machine.

Smoke uses a Unix-style file structure, so project files (other than media index and render files) are hidden from the user. This makes it difficult to move projects from one computer to the next. Smoke 2013 lives up to the commitment made at NAB 2012, but now that it’s a released product, Autodesk has a chance to hone the tool to be more in line with the needs of the target user. ©2013 Oliver Peters Posted in, Tagged,.